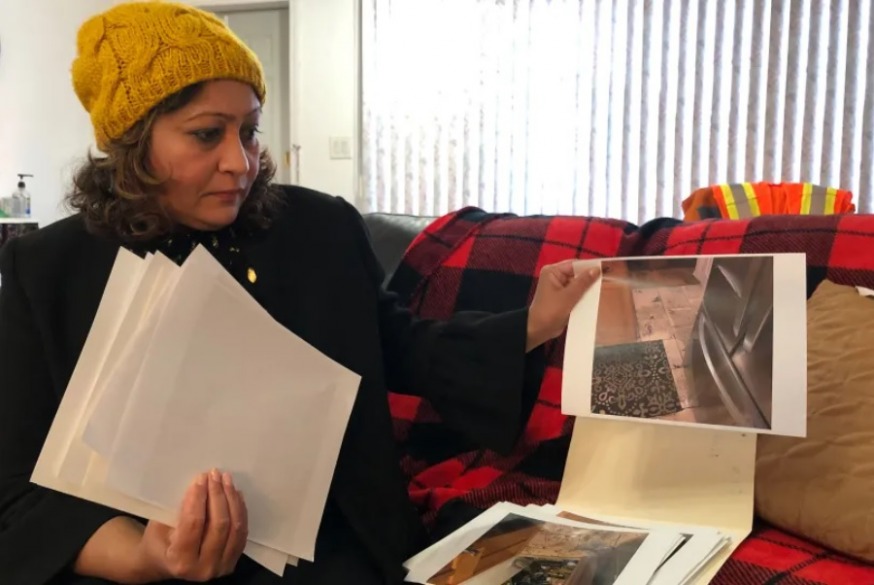

Three months after Hurricane Ida hit, Amrita Bhagwandin goes through photos that show how the storm damaged her home in Hollis, Queens. Samantha Maldonado/THE CITY

This article was originally published by The CITY on Aug. 16

Nearly a year after the remnants of Hurricane Ida flooded the Forest Hills one-bedroom apartment where Heidi Pashko and her husband live, the couple is finally beginning to settle back into their first-floor home of over four decades. That’s after living with their son’s family for about nine months and spending almost $30,000 on repairs, Pashko said.

She received a couple thousand dollars from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and filed a negligence claim against the city for damage caused by sewer overflows in the storm, in the hopes of receiving some money.

Pashko said she was “shocked” when she received a letter on Monday from City Comptroller Brad Lander completely denying her claim.

She wasn’t the only one: 4,703 New Yorkers filed claims against the city after their homes flooded during Ida. All 4,703 were denied, according to the comptroller’s office.

The crux of the claims is that the city’s negligence in sewer maintenance led to flooding damage.

The storm killed at least 13 people in New York City on Sept. 1, 2021, as it dumped over three inches of rain in a single hour on Central Park, shattering previous rainfall records — and overwhelming the city’s sewer systems, which were built to handle rainfalls of under two inches an hour.

The comptroller’s office says it investigates each claim to determine whether city negligence led to the flooding. But the decisions rely on precedent set by a case from 1907 that ruled municipal governments are not liable for damage from “extraordinary and excessive rainfalls” — even if the city’s sewer system was under capacity.

“As a result, the City of New York is not responsible for losses arising from Hurricane Ida, and your claim must be denied,” read letters sent by the comptroller and obtained by THE CITY.

Pashko said she thinks the city is “absolutely” at fault because it oversees the infrastructure.

“I could challenge it and say, ‘Well, if you had your sewer fixed, it wouldn’t be a problem,’” she said.

“No one is moving back on the first floor, only me and the super,” she said in a separate text message Tuesday. “All are paranoid and so am I when it rains.”

A typical post-flood mess: The basement in Jamaica on Sept. 2, 2021, where Abdol Hack kept his son’s wedding presents while he was away on his honeymoon. Hiram Alejandro Durán/THE CITY

As he issued the denials, Lander also pointed to ways to fix the system overall.

“I believe that the City should do more to support New Yorkers to navigate the complex array of relief programs and insurance paperwork that follow natural disasters,” Lander wrote in the denial letters.

He suggested the city develop a disaster recovery center to offer referrals to legal help, provide details about relief options and assist in submitting insurance claims.

‘I Can’t Go Anywhere Else’

Most of the claims to the comptroller came from Flushing and other neighborhoods in central and southeastern Queens.

Amrita Bhagwandin, 52, said Ida flooded the basement and up to two feet into the first floor of her Hollis home. She received her denial letter from the comptroller on Monday.

“I’m up to my wit’s end here trying to get a contractor with a decent price because everything’s going to cost me more than $125,000,” she told THE CITY. The foundation of her home was compromised, and she still has to replace plumbing and electric systems.

She’s received a few thousand dollars from FEMA, but it isn’t nearly enough to cover all of the damage, she said. And Bhagwandin is terrified of what another storm could do to her home and the rest of the city.

“It’s one year,” she said. “It is a whole year, and I just spoke to FEMA folks and said, ‘We are not ready for an emergency. We are so not ready for the emergency.’”

In an email, FEMA spokesperson Don Caetano said the agency “continuously” works with New York City and state to “apply lessons learned from previous disasters and take corrective actions to alleviate them in the future.” He declined to assess the city’s status on preparedness but said “we are collectively working to address the issues we dealt with during Ida.”

He declined to comment on the city’s denial of all the claims.

Bhagwandin’s neighbor Jennifer Mooklal said she still needs to renovate her entire basement and most of the first floor after it was flooded with water and sewage last September.

Mooklal and her family have been living in the house despite all of the repairs needed — and received their denial letter Monday.

“I can’t go anywhere else,” she said, adding that the city handled things after the storm “absolutely poorly” and the family would ideally like to sell their home.

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway near the Northern Boulevard exit in Jackson Heights was still flooded on Sept. 2, 2021. Katie Honan/THE CITY

“The city did what they wanted for the news and popularity,” she added, referring to the promises made after the storm, although she didn’t expect much governmental help after dealing with sewage floods for years.

“The city has failed us before so I’m very sure there’s no more help,” Mooklal said.

Queens Borough President Donovan Richards called for more federal infrastructure funding to fortify the borough from future storms — and also blasted the city’s handling of storm recovery.

“This decision — which I encourage homeowners to explore their options about — is an unfortunate encapsulation of the city’s negligence and sheer failure when it comes to extreme weather preparedness,” he said in a statement to THE CITY.

Those who were denied their claims and want to dispute the decision have until the end of November to file a lawsuit against the city.

A Maze of Alleged Help

Some victims of Ida have said the recovery funding and other non-monetary aid offered by government officials at the city, state and federal levels have been insufficient to cover their losses and repairs.

As of Monday, FEMA approved nearly $223 million in aid to 88,718 people statewide, with 61,696 people in New York City receiving just over $158 million, according to numbers FEMA’s Caetano provided. The average payment was $2,500.

For undocumented immigrants and others ineligible for federal aid, the state and city created a separate $27 million Ida relief fund, offering a maximum of $72,000 per eligible household. The state reopened the application period through the end of April after an initial deadline of January.

As of Monday, the state has doled out over $1.8 million to 373 applicants through the fund, according to Mercedes Padilla, a spokesperson for the state’s Office for New Americans. An additional 181 applicants also are slated to receive money, she said.

In correspondence sent Monday to the city Office of Emergency Management and the state Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services, Lander further outlined ways the government could be better positioned in the aftermath of disasters: create capacity to be able to do case management; get contracts for legal assistance for people who need it; and include post-disaster needs in the city’s larger housing plan.

OEM and DHS did not respond to requests for comment.

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.