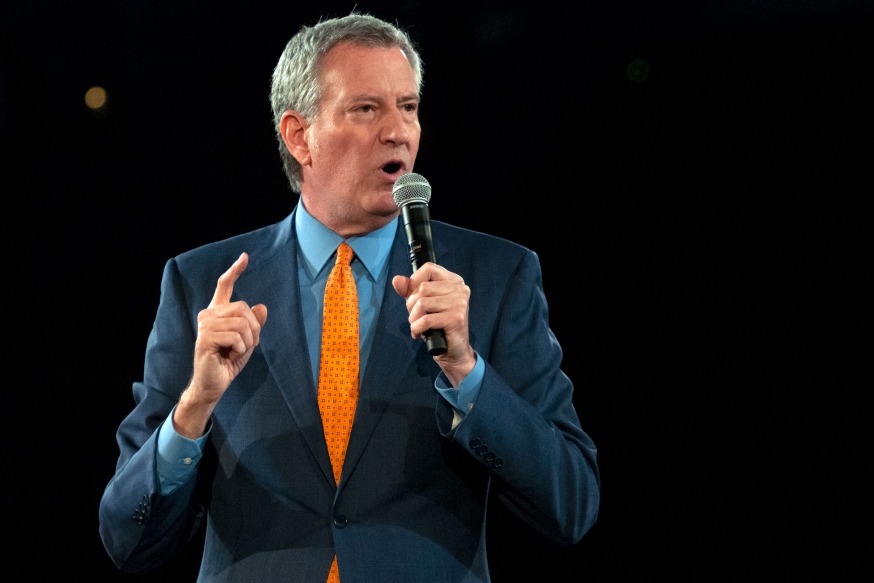

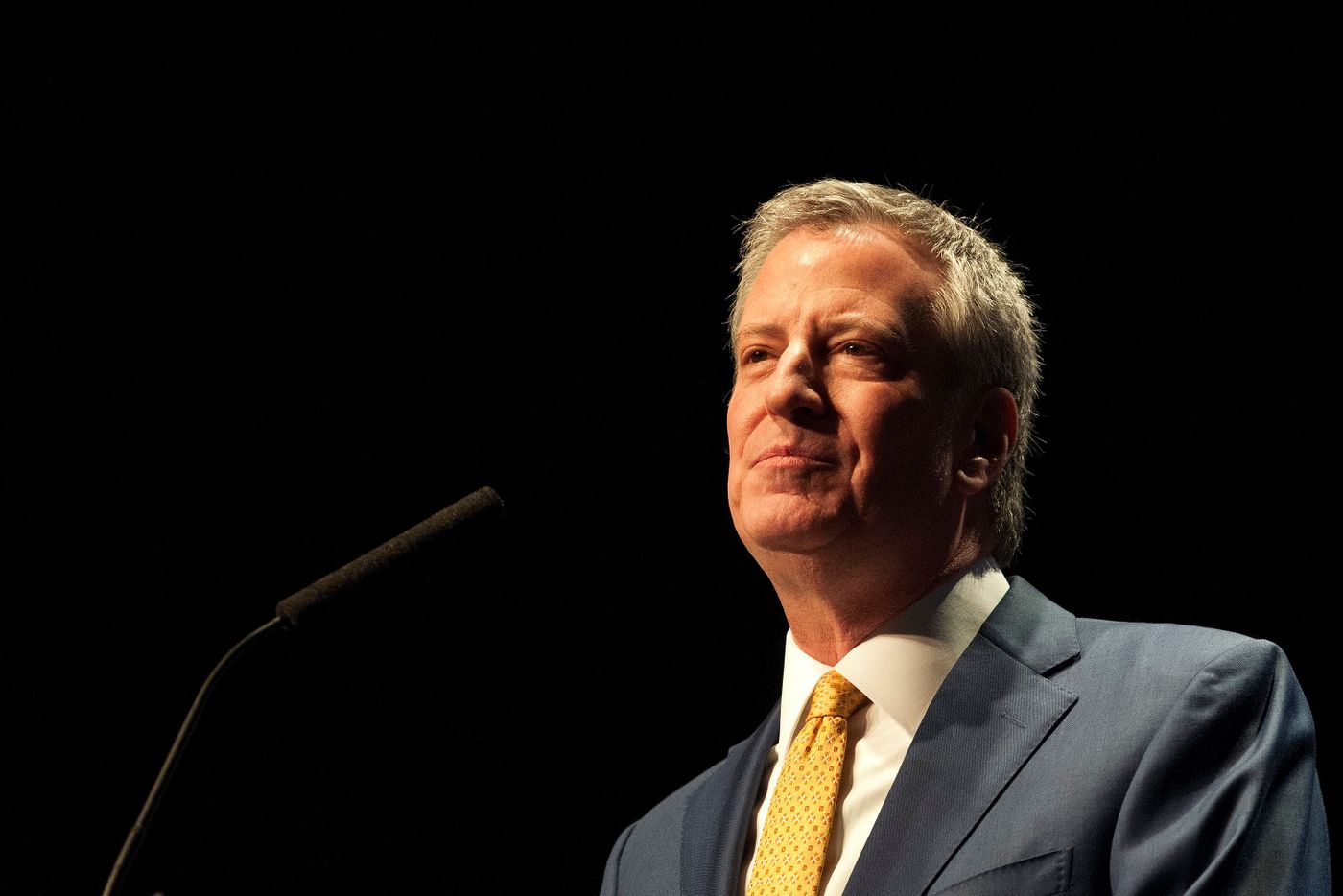

Mayor Bill de Blasio delivers his State of the City address at the Museum of Natural History, Feb. 6, 2020. | Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

This article was originally published by The CITY on Dec.20

This article was originally published by The CITY on Dec.20

By The City

In the eight years Bill de Blasio has led New York City, he’s delivered eight State of the City addresses — the annual declarations of purpose and priorities mayors use to sell their agendas.

Each year, he has used the early-in-the-year speeches — and similar events on Earth Day in April — to highlight transformative ambitions and programs, especially those aiming to reduce inequality and expand opportunity.

THE CITY looks back at eight major de Blasio announcements and where the results stand as he exits office — and possibly readies to seek a new one.

2014-15: 200,000 Units of Affordable Housing

In his first State of the City in 2014, de Blasio filled in details on his signature campaign promise to tackle the city’s long-standing shortage of affordable housing.

He pledged to “preserve or construct” 200,000 affordable units in 10 years — a number he would later expand to 300,000. But he built in a safety valve for himself: setting a deadline of 2026, well beyond his tenure.

In his second State of the City the following year, de Blasio unveiled “mandatory inclusionary zoning,” requiring that all developers seeking increased housing development rights make 20% to 30% of their units “affordable.”

Demetrius Freeman/Mayoral Photography Office Mayor Bill de Blasio Delivers his State of the City address at Baruch College in Manhattan, Feb. 03, 2015.

He also pledged to rezone entire neighborhoods to ensure affordable apartments in new development. In neighborhoods such as Inwood and SoHo in Manhattan and Gowanus in Brooklyn, he had to overcome opposition from locals worried that a wave of new buildings would alter their neighborhoods’ character — and he ultimately prevailed.

But de Blasio never obtained approval from the state or Amtrak for his 2015 State of the City proposal for 2,600 affordable units atop train yards in Sunnyside, Queens. The city housing department claims the city “remains on track” to “finance” 300,000 affordable units by 2026, including 200,000 “by the end of the administration.”

But the fine print is more complicated: as of June 2021, only 62,557 of the 80,000 “new construction” apartments he promised as part of the original 200,000 have been built.

— Greg B. Smith

2015: 90% Reduction in Waste Disposal By 2030

On Earth Day in 2015, de Blasio committed to sending no garbage to landfills and reducing waste disposal by 90% compared to 2005 levels by 2030. But today, New Yorkers are still throwing away just over 79% of garbage — compared to 83% when de Blasio took office. And we’re only disposing about 5% less waste than in 2005.

The city Department of Sanitation has acknowledged New York has no chance of achieving the zero-waste goal without a mandatory citywide composting program. “You cannot fight climate change without tackling food waste,” said Julie Tighe, president of the New York League of Conservation Voters.

Demetrius Freeman/Mayoral Photography Office Mayor Bill de Blasio unveils his “One New York” plan on Earth Day 2015.

If all New Yorkers recycled and composted perfectly, about 68% of waste could be diverted from landfills. The city currently recycles about a fifth of its municipal and residential waste, but organic material such as food scraps and leaves makes up a third of discarded trash.

In landfills, organics create methane, a potent greenhouse gas. And food scraps in plastic bags piled curbside attract rats.

Pandemic budget cuts temporarily halted limited, voluntary curbside and drop-off composting programs first launched under Mayor Mike Bloomberg. While those resumed this fall, no universal composting program is currently planned — although Mayor-elect Eric Adams backs citywide composting. —Samantha Maldonado

2016: 7,500 LinkNYC Kiosks

De Blasio touted the launch of super-fast internet-enabled, WiFi-broadcasting kiosks to replace pay phones, to be funded by ad revenue projected to bring $500 million to city coffers over a dozen years.

The mayor sought to “bridge the digital divide” by providing 7,500 kiosks within a decade — providing not only free Wi-Fi but also tablet screens enabled for phone calls, web-browsing and device-charging.

But LinkNYC, run by tech consortium Citybridge, fell short on installations — especially in the boroughs outside Manhattan. As of July 2019, it had installed 1,816 of the 2,353 kiosks that were supposed to be up and running then under its franchise agreement, THE CITY reported.

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office Mayor Bill de Blasio unveils a LinkNYC kiosk in Manhattan, Feb. 18, 2016.

The kiosks that had been installed were mostly concentrated in Manhattan, with The Bronx and Staten Island receiving 60% fewer devices than agreed to under the deal.

In early 2020, THE CITY reported at least 50 kiosks were installed but not activated.

With Citybridge owing $60 million, the city considered pulling the plug. But under an agreement amended in June, the kiosks will be retrofitted to add 5G network capabilities,and will rocket up from their current 10 feet to three stories high, counting antennae. — Gabriel Sandoval

2016: BQX Streetcar

“Shovels will be in the ground by 2019 and the beauty of this project is it pays for itself.”

That was Mayor de Blasio in February 2016, announcing details of the proposed Brooklyn-Queens Connector trolley — or BQX — that was to run from Sunset Park to Astoria near the waterfront.

He said the $2.5 billion needed for the light rail line would be funded by the increase in property tax revenue generated by the project itself along the then-16-mile route.

Demetrius Freeman/Mayoral Photography Office Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a plan for the BQX light rail line during a press conference in Brooklyn in February 2016.

Following a two-year feasibility study, de Blasio once again gave the project a green light, but with some key changes: The route would be shorter (ending in Red Hook), more expensive ($2.7 billion total) and would need considerable federal funding ($1.3 billion). Additionally, no shovels would hit ground until 2024.

That’s when the delays started. Scoping and environmental studies due in 2020 and 2021 have yet to be completed. No applications for federal funding have been submitted, according to the Federal Transit Administration.

City Hall officials said the project was paused because of the pandemic. They wouldn’t say how much money has been spent.

“The work we’ve done to date will leave the city well poised to carry the ball forward on this project and deliver fast, reliable transit options to Brooklyn and Queens as soon as financial circumstances allow,” said Mitch Schwartz, a de Blasio spokesperson.

Adams’ spokesperson didn’t respond to a question about the incoming mayor’s plan for the project going forward. Adams told NY1 in March only that he would consider it. — Yoav Gonen

2017: 100,000 ‘Good-Paying’ Jobs

Speaking at Harlem’s Apollo Theater, de Blasio made a big promise to spur New York’s job market: The city would create 100,000 “good-paying jobs” over a decade, he said.

By the city’s count, just 8,669 of those positions have been created as of June 2020, per the most recent progress report issued by the city on the “New York Works” program.

Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office Mayor Bill de Blasio delivers his State of the City address at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, Feb. 13, 2017.

The city’s results are “middling at best,” said Annie Garneva, vice president of policy at the NYC Employment & Training Coalition, a workforce development association.

Apurva Mehrotra, director of research at the Bronx-based youth employment organization Here to Here, has been disappointed by City Hall’s job efforts, too — especially when it comes to equity.

The city does not track how many newly created jobs go to city residents, Apurva said — particularly young Black and Latino locals who have unique barriers to the job market, Here to Here has found.

“The number of jobs itself, I don’t think, is nearly as important as looking at really ensuring that New York City’s young people are going to benefit,” he said.

A city Economic Development Corporation spokesperson pointed to 49,725 jobs the city projects will be created, while underscoring that New York’s economy has been wholly reshaped by the pandemic.

“While the city will continue to focus on unlocking the creation of new jobs, as we have for the last four years of the New York Works plan, these extraordinary times require that we adapt our approaches to address immediate needs and new realities,” said the spokesperson, Helen Jonsen. — Rachel Holliday Smith

2018: Car-Free Central Park

De Blasio, speaking at Brooklyn’s Kings Theatre, announced that cars would be banned from two of the city’s largest green spaces, Prospect Park in Brooklyn and Central Park in Manhattan.

He started first in 2015 by eliminating cars above 72nd Street in Central Park, and then banned vehicles from Prospect Park’s loop drive. By late June 2018, Central Park, the city’s most famous, was car-free.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY People enjoy an open street in Central Park, March 11, 2021.

“Our parks are for people, not cars,” de Blasio said in his 2018 address. Around 5,000 cars traveled through Central Park each day, the city Department of Transportation reported at the time. (The change didn’t affect three east-west transverse roadways, separated from the park.)

Parks maintenance as well as police and emergency vehicles are still allowed — including the truck that struck beloved Barry the owl earlier this year.

Some other major parks, including Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens, still allow motor vehicles on their roadways. And before exiting, de Blasio powered a notion that would have essentially returned cars to Central Park: A bill he backed would have replaced its carriage horses with antique-style electric vehicles, fulfilling his 2013 campaign pledge to ban the horses. It never reached a vote. — Katie Honan

2019: Paid Vacation for All

In January 2019, de Blasio announced his plans to guarantee two weeks of paid personal leave for about 900,000 New Yorkers — at a time when he had his sights set on a long-shot bid for the presidency.

But like that failed quest to become leader of the free world, this plan quickly fell apart.

De Blasio’s State of the City promise breathed new life to a bill first introduced in 2018 by Jumaane Williams, then a Brooklyn Council member. But the bill failed to get past committee in 2019 and was all but declared dead by the end of the year, without enough support in the Council and with trade associations claiming it would unfairly hurt small businesses.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY Mayor Bill de Blasio delivers the State of the City address on the Upper West Side, Jan. 10, 2019.

Detractors who opposed the measure claimed they were already strained by the Paid Sick Leave law approved by the City Council the year before de Blasio took office, said Irene Lew of the Community Service Society — a measure that the mayor would go on to play a key role in strengthening, she noted.

Before Paid Sick Leave took effect in 2014, de Blasio and then-Council Speaker Melissa Mark Viverito approved an expansion to include small businesses, covering an additional 500,000 workers. “He deserves credit for that,” Lew said. — Claudia Irizarry Aponte

2020: Commercial Rent Control

De Blasio’s second-to-last State of the City address had the theme of “Save Our City,” with an emphasis on preserving struggling small retailers and restaurants.

The mayor vowed to convene a blue-ribbon commission of “the best experts” to look into the idea of commercial rent control that would limit rent hikes on businesses.

The idea has been talked about for over 30 years and pushed for by advocates for small businesses threatened with massive rent increases or struggling to pay their bills.

De Blasio expressed concern during his speech at the American Museum of Natural History that the concept might not hold up in court. Nonetheless, he promised the commission would deliver its recommendations by the end of the year.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY Mayor Bill de Blasio delivers his State of the City address at the Museum of Natural History, Feb. 6, 2020.

But the rent control commission never formed. City Hall blames the pandemic.

A proposal in the City Council to create a panel similar to the Rent Guidelines Board to determine rent raises for small retailers has also gone nowhere.

During the same address, he proposed a vacancy tax on owners of long-unoccupied storefronts — something the state would have to pursue. No legislation has moved forward.

Meanwhile, empty retail space has nearly doubled between 2007 and 2017 to 11 million square feet, according to an analysis by the city Comptroller’s Office last year — before the pandemic widened the devastation. — Reuven Blau

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.